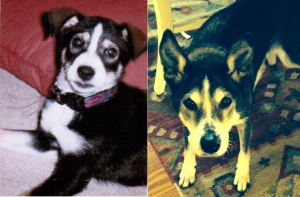

Tom wasn’t so sure about having a dog. He claims that I waited until he was at a trade show to visit the shelter in Marin, then sprung it on him that I had found Tessa and adopted her.

“Well, okay,” he sorta grumbled, when I brought her home. “But she can’t come into my office.”

I left to attend a meeting. When I returned, Tessa was sleeping on a pillow next to Tom’s desk. She had gone to the doorway to his office and stared at him with her puppy eyes. So he invited her in and got a pillow so she wouldn’t have to lie on a hardwood floor.

Eight-week old puppies don’t do that—wait at the door. But somehow, Tessa understood Tom and so asked to be invited into his heart.

The night Tom’s mother died, we brought Gene, his father, back to our house after the long day of making arrangements. He dropped his 88-year old body onto the couch. Rug, our aptly named cat, jumped onto his lap, and Tessa curled herself up next to him. It was their furry bodies that kept Gene from floating away that night.

Tom’s father and my mother became the flock Tessa attended to when we moved to Livermore, following them if they left the room, gently grabbing their wrists to bring them back to us. She sang as Tom played the piano the night my mother died, but with a soft mournfulness rather than her usual exuberance.

I don’t know how dogs know these things, but they do. And Tessa was a mix of herding breeds, so she was especially tuned to communicating with the humans in her pack.

In her heyday, she kept up with the whippets at the dog park. She leapt like a deer through what Tom’s daughters named Oberon’s Meadow. She would gleefully chase the ball then negotiate with Tom as to whether she should return it to him or he should come get it from her.

It wasn’t until she was fifteen that things changed. I had woken in the middle of the night on Valentine’s Day and as I made my way to the kitchen for a drink of water, I saw Tessa huddling under the dining room table, unable to move her back legs, her eyes wide with terror, her front legs spread apart to hold her up.

Our vet told us she had something called Old Dog Syndrome—or to be more precise Old Dog Vestibular Syndrome—similar to Meniere’s disease or vertigo in humans. Basically, gravity ceases to exist. The world loses its stability so there is no context for determining which end is up—or sideways for that matter.

The vet reassured us that Tessa would likely recover completely with some tender loving care on our part—we fed and hydrated her by hand, and carried her to the yard so she could urinate and defecate. She would wait until we were by her side before she attempted to walk, would look back at us if we fell too far behind, letting us know that our presence helped her find her grounding.

One of the most endearing traits of dogs is their loyalty. In a way, the tables were turned as we nursed her back to health. She had to rely on our loyalty to her—our willingness to stay by her side as she regained her equilibrium.

It was a little over a year after her bout with Old Dog Syndrome that we sold our home in California and moved to Washington. We worried how it would affect her, the constant presence of strangers streaming through her home as we prepared for the sale. And then there was the long drive from the Bay Area to Sequim. She was over 16 by then.

But survive and thrive she did. There were the occasional spurts of running through the yard, but mostly what we noticed was the comfort of having her with us—the three of us settling into our daily routine. She would walk with me to the mailbox in the morning to get the newspaper and in the afternoon to fetch the mail. Each of us would give her a treat as we made our morning cappuccino, then one or the other of us would make what we came to call her breakfast—her medication dissolved into chicken broth with some thinly sliced roast beef we got at Costco added to perk her interest.

Why wouldn’t she want to stick around?

But she was slowing down. The last few months, she spent much of her day sleeping on her bed in our bedroom. She began to linger halfway down the long driveway when I walked to the mailbox. At night, when Tom played piano, instead of singing, she paced though the house, as if searching for the song that lingered in her memory.

And still, she was there, the herding dog who cared for her flock. During the weeks between our learning of Tom’s high PSA, the tests, and waiting for results, Tessa hovered near Tom.

The end came quickly and gently for Tessa. On Wednesday, May 6th, I took her in the morning to the groomers. At noon, Tom drained the olive oil from the sardines he would have for lunch onto a few bites of her dry food—Good news for Tessa Dog we called it. And it was—she ate it joyfully.

And then she stopped eating. Refused her afternoon treat. Wouldn’t eat her dinner. During the night, she vomited. The next morning, she went into Tom’s office and brushed against him, lingered, then came to my office, brushed against me, lingered, then began looking for a corner, a sheltered place.

We got her outside into the yard where she roamed. The vet came by and confirmed what I thought was happening. Tessa was dying.

“They don’t like dying in the house,” said the vet, who had stopped by on her way to tend to another animal. We were committed to Tessa dying at home and the vet couldn’t come by until the next day. Since Tessa was not in any distress, we decided we could wait.

As soon as the vet left, Tessa made a beeline to the house where she lay down in our bedroom.

By the next morning, she had made her way to the door to the sunroom, but could not make it any further. So we carried her to the yard and placed her on the ground surrounded by four tall trees. Tom and I sat vigil.

It was one of those quiet just slightly warm spring days. The world seemed to stop but life continued around us. Birds chattered. We could hear the occasional lowing of the cows across the road. Tessa breathed easily.

Tessa was pretty much gone by the time the vet arrived at noon. I lay down next to her, placed my hand on her chest, and felt the final soft beats of her heart.

Yesterday, two and a half weeks later, we got the results from Tom’s PSA test—his first since he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and began receiving hormone suppression treatments. It was down 90% —to a level considered normal for a man his age. He will be starting radiation treatments in a few weeks—the radiation holds the promise of being curative.

Yesterday morning, before we left to meet with the radiation oncologist, a deer came into our front yard. Deer sightings are common, but this was the first time I had seen one in our front yard. I thought of Tessa leaping like a deer through Oberon’s Meadow.

We feel we have cancer on the run. With all of the support Tom has received from friends and a team of professionals that includes my dear friend, Nancy Wheeler—a hypnotherapist—we think the cancer is outnumbered. I no longer have that cold gut-wrenching fear of losing Tom.

I knew when I wrote the blog about Old Dog Syndrome, that I would one day have to write about Tessa leaving. I knew I would title it, “And Then it Was Time for Her to Go.” Knew I would have to let her go for she would know it was time.

Tessa stayed with us as long as she could. And, we believe that she stayed long enough to make sure that Tom would be okay—and that I would be okay. Dogs, they have discovered, can smell the presence of tumors, so it is not far fetched to believe that she sensed that her flock was out of danger.

Her absence is still a presence for us. We still expect to see her lying on her bed when we enter the bedroom. Making her breakfast is a missing piece in our mornings. We miss her walking down the driveway to help us fetch the paper and mail.

I attended a workshop last week offered by the cancer center affiliated with our provider. Two people with cancer talked about their loss of independence, what it feels like to have to depend on others for things they did for themselves.

I thought back to that day when Tessa, in the midst of Old Dog Syndrome, looked back at us to make sure we were close by—a look that said she knew she could not tend to the flock as she once had. We assured her that we wanted her around regardless. We loved her. She could depend on that.

Her last few years brought great comfort to Tom and me. Three sentient beings, spending our days confident in the knowledge that we cared and could depend on each other, and on our loyalty to love and what love asks of us.

In the end, it was quiet.

My hand over her heart, feeling it stop

—like the sound of falling snow.

I hate this and I love this. I hate that it always must be this way, but I love that she brought you such emotions, and memories. Beautiful post.

LikeLike

I know. It is the way it must be. Thank you for your lovely, kind response.

LikeLike

Beautiful, touching story of Tessa and the 2 humans love. I am grateful to have known her and seen her near the end. She gave and received such love we can all learn from. Thank you ,for the reference to me in your story. I am touched and relieved in the validation of the power of love. Live long and prosper my dear friend (s)💗

LikeLike

Loved reading this beautiful story. You guys took good care of each other, and continue on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank, Holly. She was a good dog.

LikeLike

I have no words. Beautifully lived, wonderfully loved, and peacefully passed. Love to you and Tom.

LikeLike

Thanks, Laura. It’ heartbreaking losing a dog. Hope you are well.

LikeLike

Tears in my eyes for Tessa…and gladness in my heart for Tom. Just so much contained in these lovingly written paragraphs…

LikeLike

Thank you, Suellen.

LikeLike

Love to you, and to Tom, and to Tessa, wherever she is leaping and running now. Your words brought tears. The love you and Tom have for her is clear, as is her love for both of you. So sorry you had to say goodbye~

LikeLike

Thanks, Selene.

LikeLike

Simply beautiful.

Hugs.

LikeLike

Thank you, Carol.

LikeLike