Tom moved his strong purposeful fingers across the piano keys. The music we had heard the day before, as we watched the pine trees move to the graceful rhythm of the late afternoon wind, filled the room.

Tom moved his strong purposeful fingers across the piano keys. The music we had heard the day before, as we watched the pine trees move to the graceful rhythm of the late afternoon wind, filled the room.

His magic never ceases to amaze me: he hears music before anyone else. He didn’t create the sound of the wind through the trees; he created the music they made.

We had returned the day before from a weekend with Owen Goldsmith, our high school music teacher, who had retired several years ago, bought some land in the Sierra foothills, and built an A frame.

On Saturday he took us to see the “big trees” — the grove of giant sequoias whose trunks are wider than city streets and rise as high as a twenty-six story building. Their limbs, lush with evergreen vegetation, don’t begin to appear on the trunk for hundreds of feet above the ground. I stared up from the base of one and imagined the world that this magnificent being harbored, the fairy people or the Ewoks perhaps.

The trees are as old as three thousand years; standing still in their daily lives while human civilizations rose and fell. I could sense the presence of time.

This is my cathedral. My Vatican. My Chartres. My Notre Dame. I was in the presence of the sacred. It’s impossible to feel alienated in their presence.

We wandered into the park’s Visitors’ Center, where we learned that the indigenous tribes revered the trees, and where the story of the trees’encounters with the mid-nineteenth century invaders are recorded. Infected with gold fever, they saw the trees as they saw the indigenous tribes, an end-of-the-frontier phenomenon to conquer; an entrepreneurial opportunity to exploit.

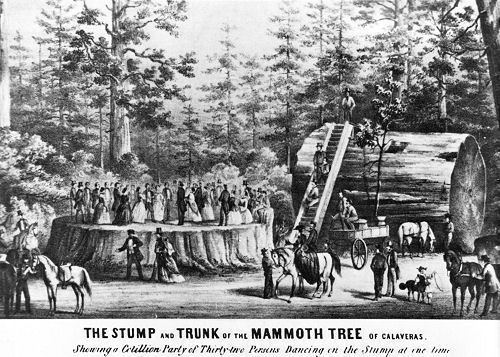

One photograph shows a dance hall that had been built on a stump. The tree had been cut down just so they could prove that it was large enough to put a dance hall on it.

Another story describes the fate of the “Mother of the Forest.” Estimated to be 2500 years old in the 1850s, it was one of the largest and oldest trees they came upon. Working for ninety days, a crew removed its bark in eight foot sections, up to a height of 150 feet. The sections were shipped around Cape Horn to New York and then on to London where the sections were put together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle so Crystal Palace audiences could pay to get a glimpse of the size of the trees that grew at the end of the frontier.

Apparently I was wrong. It was possible to feel alienated amongst the majesty of the trees.

As we wandered deeper through the grove, we came upon the Mother of the Forest. We hadn’t realized that her skeletal remains still stand, a sesquicentenary later.

Unprotected by the canopy of her own lush branches, she stood alone and separated from the other sequoias. Her mutilation was obvious; a raped woman, her shame and humiliation exposed for all to see. I had to avert my eyes.

We drove back to Owen’s in silence.

Later, we sat on his deck, drinking wine and talking the way people who have been friends for more than forty years talk — recounting memories, enjoying the present, looking forward to the future with each other. We watched the deer come and eat from his deer feeder and listened as the two pine trees at the edge of his property moved rhythmically with the wind — the music Tom captured when we returned home.

“The trees grow like that in pairs,” Owen told us. “If one of them gets invaded by a pest, it secretes a sap that heals its wound. The wind carries the scent of the sap to its mate, alerting it to the invader, so it can produce a chemical that deters the pest from invading it. The forest protects itself that way. It’s similar to the way we communicate with pheromones.”

A couple of days after we returned, as I sat in a café, the memory of Tom’s music, the mated pine trees, the giant sequoias, and the folly of the gold-seeking entrepreneurs fresh in my mind, a man sitting at the next table began telling his companion about his latest venture — a lumber company in Russia.

“I’m an entrepreneur. I live to take risks,” he said proudly, stirring his cappuccino.

My stomach knotted.

“The youngest trees in this forest are three hundred years old; some have been standing for 400 years or more.”

Since Shakespeare wrote.

“The wood from these trees produce lumber that’s denser and has a finer grain than the lumber we can harvest here,” he explained to his companion. “I stand to make a lot of money.”

These trees don’t have the language to warn each other of the coming invasion.

I wondered what songs his forest created when its trees moved with the wind. What it sounded like when its coupled trees, bonded together in ancient marriages, spoke to each other, recounting their daily lives.

What was it like when they heard the deafening buzz of the saw? When she had to watch as the metal teeth cut through her mate; heard the splintering cry as he, who had been her companion for 400 years, fell to the ground.

Was she grateful when the metal teeth began chewing through her skin? Could she bear the loneliness of losing the mate she had been bonded to for 400 years?

What will become of us when we have destroyed the stories of all other living creatures, silenced all their songs? Will we have any soul left to tell our own stories, compose our own songs?

The entrepreneur and his companion disappeared into the dark outside the café. Tom’s music found its way through the sterile stillness emanating from the mutilated landscape I imagined in my mind.

I was grateful I had him to go home to.